It is highly misleading to think of billionaires’ money as exclusively their own. There are two reasons for this. First, factor costs (such as for labor, education, resources, and transportation) that are critical to corporate success are subsidized by governments and taxpayers. Yet corporations and billionaires do not sufficiently reinvest in these infrastructures via taxes, wages, and local investments. Second, and relatedly, US laws allow billionaires to voluntarily invest in philanthropic foundations as a way of sheltering money from taxation.

To begin with, billionaires’ companies are only able to function because of public goods and investments. As an example, Amazon relies on publicly-funded roads and highways. Yet tax rates for wealthy individuals and corporations have progressively decreased. This means that while these companies and individuals benefit from and rely on public road networks, public education (of workers, for example), and other publicly-funded goods and services, they pay proportionally less into supporting or maintaining those systems.

Changes to tax law from the late 19th to mid-20th century created exemptions for philanthropic foundations, under the assumption that they act in the public good and are by definition nonprofit organizations. Not only is the money set aside in private charitable foundations untaxed, but in some periods, the government has allowed individual income tax deductions for charitable contributions. Most early philanthropies were founded by the same monopoly capitalists and industrialists who aggressively exploited workers and engaged in political corruption. Unlike earlier voluntary associations, these philanthropic foundations typically relied on one source of wealth, being centered around a particular industrialist and that industrialist’s family. As Andrew Carnegie articulated, the wealthy should reinvest some of their money, but toward causes that they themselves determine worthy:

trust funds, which he is called upon to administer, and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial results for the community.

By emphasizing voluntarism over compulsory and progressive taxation, the tax structure empowers the wealthiest individuals and their non-democratic foundations to make decisions for the rest of us.

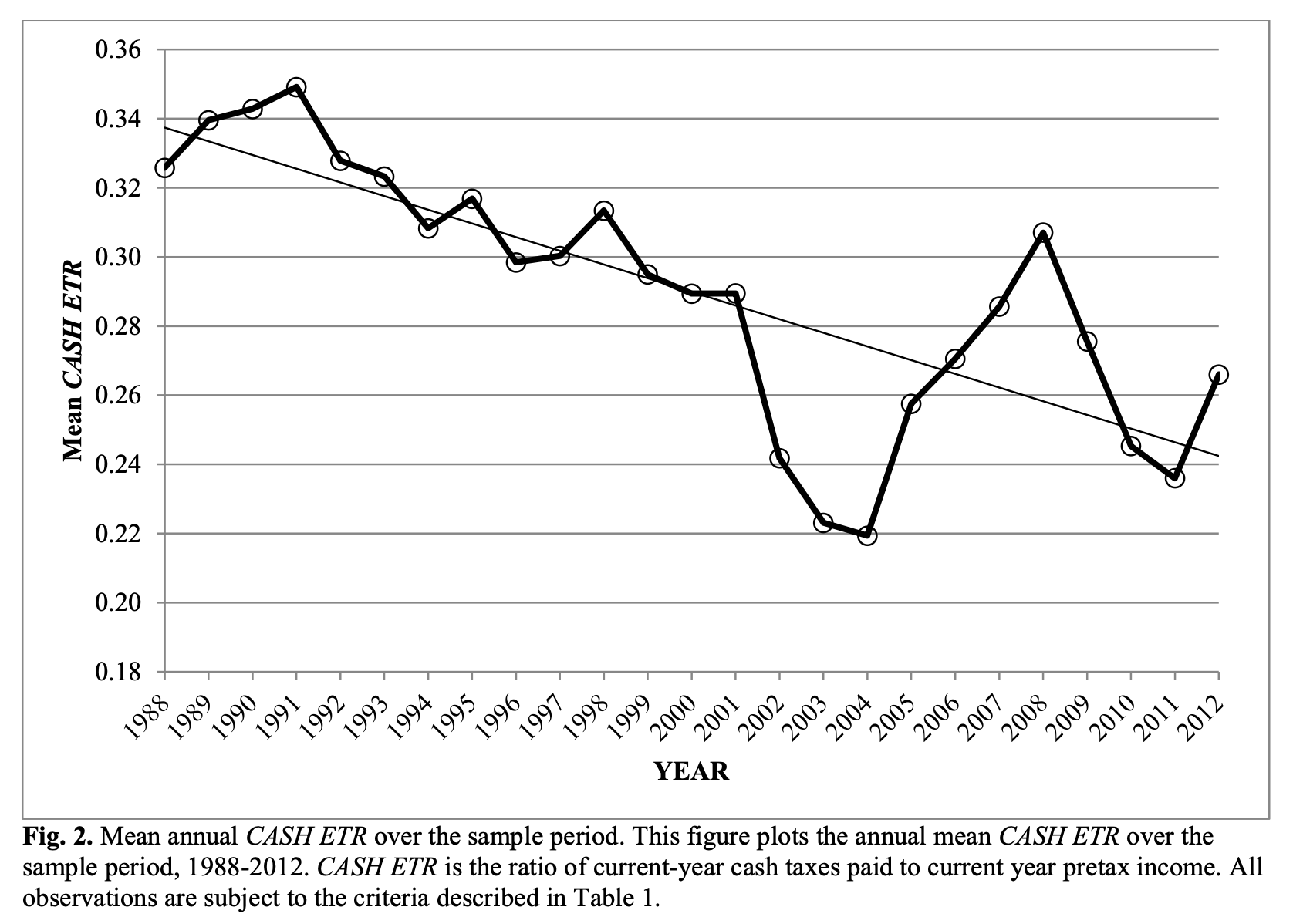

And this has only gotten worse with subsequent changes to tax policy. Corporate tax rates and taxes on the wealthy have decreased since the 1950s, with dramatic declines under neoliberalism from the 1980s onward. And while some billionaires, like Warren Buffett (and Gates himself), have suggested that the wealthy should pay higher taxes, Gates has pushed back against actual proposals to do exactly this—most notably, Senator Elizabeth Warren’s progressive wealth taxation proposal in 2019.

Effective corporate tax rates have declined since 1988. (source: Scott Dyreng et al., 2016, forthcoming)

By using various loopholes and creative accounting, many profitable corporations are able to avoid income tax entirely. (source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2017)

It is therefore important to remember that billionaires’ money is not simply “their own,” over which the public should have no say. They have earned this money at least in part due to reliance on public infrastructures and services, and through neoliberal policies that have decreased corporate and wealthy tax burdens, while keeping workers’ wages and salaries stagnant. And through tax laws, these billionaires have been granted the privilege of voluntarily contributing to charity (in exchange for further tax write-offs and exemptions), rather than being compelled to pay more into public systems that benefit all of us and that are, in theory, governed through public and democratic processes.

SOURCES

Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (Oct 2 2019), How a Federal Wealth Tax Can Help the Economy

Christopher Ingraham (Oct 8 2019), For the first time in history, U.S. billionaires paid a lower tax rate than the working class last year, Washington Post

Paul Arnsberger, Melissa Ludlum, Margaret Riley, and Mark Stanton (2008), A History of the Tax-Exempt Sector: An SOI Perspective, in Statistics of Income Bulletin

The Gospel According to Andrew Carnegie, Lapham’s Quarterly

Sergei Klebnikov (Nov 9 2019), Bill Gates Becomes Latest Billionaire To Grapple With Elizabeth Warren, Forbes

NOTES

There is some debate about the economic effect of decreasing corporate tax rates and tax evasion. Some, like Elizabeth Warren and progressive think tanks, highlight the economic cost of lower effective tax rates and of loopholes that allow some of the most profitable corporations in the US (including tech companies, energy companies, and oil and gas companies) to pay zero taxes, often year after year (see, e.g. Elizabeth Warren, Apr 11 2019, I’m proposing a big new idea: the Real Corporate Profits Tax, in Medium, and the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (2017), The 35 Percent Corporate Tax Myth). By contrast, right-wing and tax-avoidant institutions like the Cato Institute suggest that while corporate tax rates have in fact decreased, corporate tax revenues have actually increased, because of a higher percentage of companies listed as S-corporations or pass-through entities (rather than C-corporations).