The seed laws currently being passed protect companies, not farmers. In fact, they heavily restrict farmers’ practices and negatively impact the informal seed sector, which is highly efficient and culturally important.

In some cases, national plant varieties protection (PVP) laws even make it illegal for farmers to save or exchange saved seeds of patented varieties.

“Awareness-raising” ads about the dangers of illegal seeds, by major agribusiness industry association CropLife International, which promotes chemical fertilizers, biotechnology, and seed patenting (source: CropLife International)

While some national laws offer nominal protections for what is referred to as “farmers’ privilege” (i.e. the continued ability of farmers to replant seeds on their own land), there are various definitional ways that farmers’ rights, cultural practices, and generational and Indigenous knowledge are hindered. For instance, many countries’ seed laws do not define marketing or selling as restricted to monetary transactions alone, but also include bartering or free exchange. South Africa’s Plant Breeders Rights’ Amendment Act of 1996 suggests that farmers are exempted from plant breeders’ rights protections only insofar as they are using the varieties only on land occupied by them and do not share said varieties for “propagation by any person other than that farmer.” But South Africa’s updated 2018 Plants Breeders Rights Act defines “selling” a plant variety as not only limited to monetary transactions but also “to exchange or to otherwise dispose of to any person in any manner”—which means that restrictions against selling seeds for which one does not hold a license could also be enforced against those giving away seeds. As such, these regulations may mean that traditional practices of exchanging and saving seeds could be interpreted as infringing on plant breeders’ rights. Additionally, the 2018 act suggests that subsequent decisions by government ministers can determine the size and type of farmers who can benefit from “farmers’ privilege,” the crops these exceptions do or do not apply to, and the uses to which these seeds may be put.

PVP laws in other countries, including Nigeria and Ghana, include similar exemptions for farmers to use protected seed varieties for “personal use on their own holdings,” so long as it is for private and “non-commercial” ends. This provision, common in many PVP and plant breeders’ rights (PBR) laws, is further clarified by UPOV:

“The propagation of a variety by a farmer exclusively for the production of a food crop to be consumed entirely by that farmer and the dependents of the farmer living on that holding, may be considered to fall within the meaning of acts done privately and for non-commercial purposes. Therefore, activities, including for example “subsistence farming”, where these constitute acts done privately and for non-commercial purposes, may be considered to be excluded from the scope of the breeder’s right, and farmers who conduct these kinds of activities freely benefit from the availability of protected new varieties.“

“UPOV Contracting Parties have the flexibility to consider, where the legitimate interests of the breeders are not significantly affected, in the occasional case of propagating material of protected varieties, allowing subsistence farmers to exchange this against other vital goods within the local community.”

The problem with these formulations, however, is that very few farmers meet these strict, narrow definitions of subsistence farming, often selling at least a small portion of their harvest. It is thus unclear and vague under what conditions small-scale farmers’ saving, replanting, and sharing of seeds are exempted from plant breeders’ rights laws.

Furthermore, protecting plant breeders’ rights over and above farmers’ rights often ends up privileging outside firms. Around 60 percent of those institutions or individuals who held plant breeders’ rights in South Africa as of 2011 were foreigners based in Europe and North America. At the same time, it has proven nearly impossible to reconcile UPOV-compliant laws with other international treaties guaranteeing access and benefit-sharing (ABS). The traditional landraces that serve as the parent material for new varieties often do not meet criteria for distinctness, uniformity, and stability; as such, there are no provisions or mechanisms in many plant varieties protection laws and plant breeders’ rights laws for benefit-sharing or recognition of traditional or Indigenous knowledge and crop breeding.

Corporations and institutions are also able to profit from as-yet unpatented African seeds, which have been domesticated collectively over many generations. At the same time, these corporations use collaborations with public research institutions like the Consortium of International Agricultural Research Centers (CGIAR) to help them access germplasm and develop a favorable policy environment for the commodification and privatization of seeds.

Map of agricultural research centers that are part of the CGIAR network (source: CGIAR)

How does this work?

Crop breeding initiatives (including those that employ biotechnology) do not create seeds from out of nowhere—they require parent material. Most commonly, they get this parent material through seed banks, many of which are housed in CGIAR centers around the world. These seed banks include large amounts of diverse donated seeds, and historically have been free and accessible to all, based on the idea that they are part of the common heritage of mankind.

Researchers, companies, and institutions then manipulate this parent material in order to produce novel varieties of seed. Then, they patent the novel varieties of seed, and are able to generate private profits from selling it and licensing its production. This is a form of what has been referred to as biopiracy—the theft of public seed and biological resources for the benefit of private companies. Biopiracy can happen in a variety of ways: researchers could use Indigenous knowledge of a plant’s medicinal qualities to then extract a compound that can then be used to synthesize, mass produce, and sell a pharmaceutical product, or a company could use a naturally-occurring or domesticated plant with particular fungicidal properties to create commercial fungicides (as happened when the US Department of Agriculture and multinational corporation W. R. Grace attempted to patent a plant treatment made from the extract of seeds of the neem tree).

As an example of how this has worked in reference to seed banks, in 2009 the International Center for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas (ICARDA), a CGIAR center, entered into a 3-year research agreement with Impulsora Agrícola, a Mexican firm that acts as an agent for three breweries, one of which was acquired in 2010 by Heineken and the other two of which are companies owned by Grupo Modelo, itself partially owned by the massive Anheuser-Busch. The international seed bank allowed exclusive private control over the barley lines required to develop new varieties and “elite germplasm” adapted to Mexico, for the benefit of beer production; this meant if requested by the company, distribution of the barley lines of interest would be withheld from any other party in Mexico. Rather than offering any concrete benefit sharing agreement that would redistribute any future profits from the new variety, the agreement vaguely suggested that any improved progeny would eventually be shared with farmers through an “international public goods spill-over.”

As another example, in 2014 the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and Bioversity International attempted to “crowd-source” farmers’ knowledge of stress-tolerant and climate-adapted crop varieties, via a public online survey. This survey encouraged agricultural researchers, farmers, and people working with farming communities to provide detailed information about hardy crop species that would enable the group to “prioritize crops for climate change adaptation research and strengthen market links of stress-resistant crops.” Yet the survey contained no mention of acknowledgement or benefit-sharing, were any of this information to result in successful climate-resilient cultivars being developed and commercialized.

Legally, corporations and institutions are obligated to follow access and benefit-sharing agreements, as mandated by the Convention on Biological Diversity and the International Treaty for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, which would redistribute some of this profit back to the farmers who originally bred the parent seeds. In the case of many new varieties bred from germplasm donated to CGIAR seed banks, no benefit sharing has occurred. Increasingly, these crop breeders have been granted exemptions to ABS agreements.

Diagram showing how ABS works (source: UN Convention on Biological Diversity, modified in Hasrat Arjjumend (2015), Analysis of India’s ABS Regime in Context of Indigenous People and Local Communities

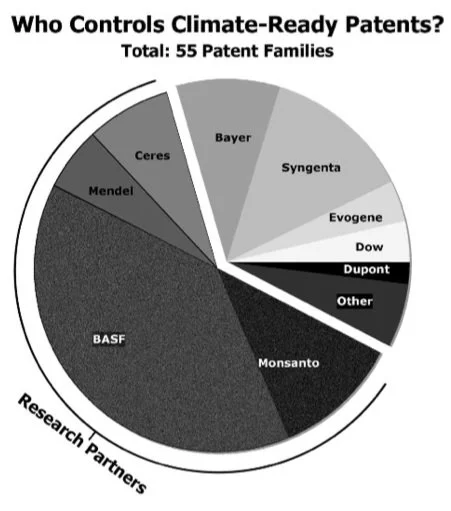

Control over climate-ready crop patents, as of 2008 (source: ETC Group)

In addition, many of these public seed banks and the CGIAR as a whole have been increasingly privatized, largely as a result of Gates Foundation funding since 2007. By 2010, the CGIAR system had structurally transformed to reflect a focus more on economic returns and cost-benefit analysis than on its original purpose as a public and social good. The function of the board of directors, for example, was converted from an advisory role serving scientists and crop breeders, into the central decision-making body, made up of members handpicked by the Gates Foundation—including Marco Ferroni, CEO of the Syngenta Foundation. Additionally, a restructuring of voting power granted more votes to Europe (which has seven votes, compared to only one each for the entire regions of Pacific Asia, South Asia, West Asia, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa), and granted a full vote to only one non-governmental entity: the Gates Foundation. This means that the weight of the Gates Foundation’s vote is equal to that of the entire region of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Main funders of CGIAR Trust Fund, as of 2017 (source: CGIAR, via Regeneration International)

Sources and additional reading:

UPOV (2006), Plant Variety Protection Gazette and Newsletter

La Via Campesina (8 Apr 2015), Seed laws that criminalise farmers: resistance and fightback, GRAIN

Republic of South Africa (1976), Plant Breeders’ Rights Act, with amendments through 1996

Republic of South Africa (2011), Plant Breeders’ Rights Policy

Republic of South Africa (2018), Plant Breeders’ Rights Act

Republic of Ghana (2013), Plant Breeders' Bill

UPOV (2009), Explanatory Notes on Exceptions to the Breeder’s Right under the 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention

UPOV (nd), Frequently asked questions

Florian Rabitz (2017), Access without benefit-sharing: Design, effectiveness and reform of the FAO Seed Treaty, in International Journal of the Commons

Vandana Shiva (2016), Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge

ETC Group (Jan/Feb 2012), The Greed Revolution: Mega Foundations, Agribusiness Muscle in on Public Goods (Communiqué no. 108)

Andrew Mushita and Carol Thompson (2019), Farmers’ Seed Systems in Southern Africa: Alternatives to Philanthrocapitalism, in Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy

ICARDA (30 Sept 2011), Breeding activities of the ICARDA Barley Program in Mexico

CGIAR (28 Jan 2014), Share your crop knowledge: Help identify stress-tolerant species, Bioversity International and CIAT