UPOV is not the only model for developing IPRs, but it has become hegemonic due to pressure from institutions, governments, and corporations based in the Global North.

WTO TRIPS (Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights) council (source: WTO)

As a condition of WTO membership, African countries are required to implement some kind of intellectual property rights (IPRs) protections. However, there are different proposed models for how to do this. Among them are two competing and opposing frameworks: the 1991 International Convention on the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV), and the African Model Legislation for the Protection of the Rights of Local Communities, Farmers, and Breeders, and for the Regulation of Access to Biological Resources (also known as the African Model Law). However, this latter model law has been continually quashed by foreign interests and pressure from AGRA and other institutions.

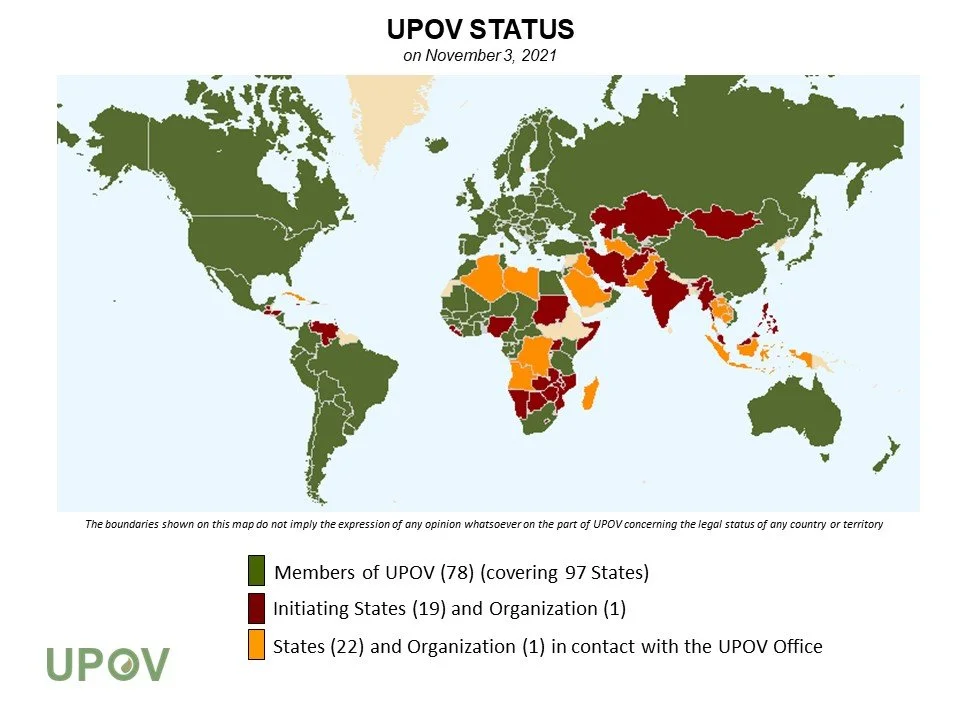

UPOV is both an international agreement and an organization that seeks to delineate and protect intellectual property rights over new crop varieties developed by crop breeders. Initially created in 1961, the agreement was revised numerous times—most notably in 1991 (this iteration of the agreement is often referred to as UPOV 91 and paved the way for seed privatization). Countries that have signed on to UPOV are expected to pass plant varieties protection (PVP) laws, which are designed to promote the development of new seed varieties by allowing the patent holder to determine who may have licenses to sell that particular variety of seed. UPOV initially faced widespread rejection by communities, organizations, agricultural entrepreneurs, and countries, because of how the convention converts public, communal, and culturally-significant plant resources into private property. By 1968, only 5 countries had ratified the convention, and at the time of the last revision in 1991, only 20 countries were members. Since this time, countries in the Global North have persuaded non-industrialized countries to ratify UPOV by including it in bilateral or regional trade agreements. As a result, 76 countries and 1 organization (the Africa Regional Intellectual Property Organization, ARIPO) have ratified the convention. In July 2015, ARIPO adopted the Arusha Protocol for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, creating a regional framework for plant variety protection (PVP) that is in partial compliance with UPOV. As a result, many individual countries that are part of ARIPO are in the process of instituting laws that comply fully with UPOV. UPOV strongly prioritizes the rights of professional breeders over farmers practicing in situ crop breeding.

The African Model Law was approved by the Organization for African Unity (now the African Union) in 2000. The African Model Law met TRIPS requirements while also protecting farmers’ rights. It rejected plant patents and the wholesale adoption of UPOV. Yet the African Model Law has not been adopted by any African country.

Countries with membership in UPOV, as of November 3, 2021 (source: UPOV)

The Gates Foundation has actively funded programs that push for UPOV-compliant seed laws and policy interventions, both through Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) and through other grants. AGRA has been extremely influential in getting national-level plant varieties protection laws passed. AGRA and other proponents of these laws refer to this as “harmonization,” and AGRA has directly lobbied for seed laws to be passed, as well as funding other grantees who do this work. From 2015 to 2018, AGRA invested in promoting seed law harmonization in Burkina Faso. And from September 2018 to November 2019, AGRA invested US $235,470 in Nigeria’s National Agricultural Seed Council for the development of plant variety protection laws in line with the interests of major plant breeders and UPOV. The influence of AGRA and other corporate and intergovernmental actors is also clear at the regional level. For example, as a result of the involvement of these actors, the African Union recently passed restrictive, pro-industry seed policy frameworks that undermine civil society and farmer-managed seed systems, which supply the majority of seeds on the continent.

A number of movements have sprung up across the globe to resist UPOV-compliant PVP bills and other laws eroding farmers’ food sovereignty. In Ghana in 2014, civil society and farmer organizations expressed serious concerns about the government’s adoption of a bill based on UPOV 1991 and the intention to join the convention without public consultation. The bill was contested for undermining farmers’ rights and enabling the entry of GMOs. In Nigeria in 2021, hundreds of farmer groups, civil society organizations, and women protested against the new plant varieties protection bill that would bring the country in compliance with UPOV (Nigeria ultimately upheld the law and was admitted to UPOV in August 2021).

Nnimmo Bassey of HOMEF, an environmental organization that led the Nigerian protests against UPOV membership (source: Prime Business Africa)

Sources and additional reading

Alianza Biodiversidad and GRAIN (6 Apr 2021), UPOV: The Great Seeds Robbery

GRAIN (2015), UPOV 91 and other seed laws: a basic primer on how companies intend to control and monopolise seeds

Titilayo Adebola (2020), Africa and Intellectual Property Rights for Plant Varieties, in Oxford Bibliographies

Titilayo Adebola (2020), Mapping Africa’s Complex Regimes: Towards an African Centred AfCFTA Intellectual Property Protocol, in African Journal of International Economic Law

ITAD (2020), Mid-term evaluation of AGRA’s 2017–2021 strategy implementation

KIT Royal Tropical Institute (2020), Nigeria Outcome Monitoring Report 2019, AGRA-PIATA Programme

African Centre for Biodiversity (2021), Harmonisation of seed laws in Africa

African Centre for Biodiversity (23 Feb 2021), African Union endorses draconian, undemocratic and corporate captured policy guidelines for seed and biotechnology for the continent

APBREBES (2014), Massive Protests in Ghana over UPOV style Plant Breeders' Bill

Edu Abade (9 July 2021), CSOs reject GMOs in Nigeria, seek urgent review of NBMA Act, The Guardian

Margaret Le Galle (18 Oct 2021), Nigeria's plant variety protection: in line with international IP norms, Managing IP

Watch:

UPOV: The Great Seed Robbery (GRAIN)