After over 50 years of Green Revolution programs that promised to increase yields and feed the world, hunger has not disappeared globally, nor in many of the countries heralded as Green Revolution “success” stories.

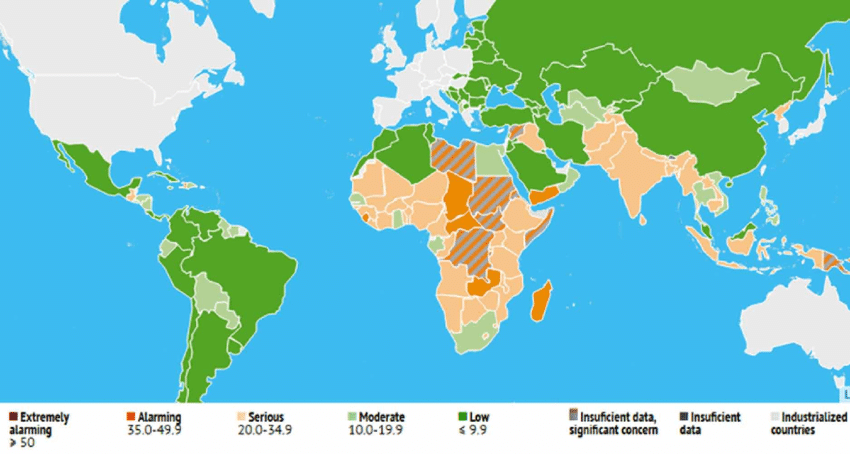

Figure 1: Map of the Global Hunger Index in 2016 (source: Von Grember et al., 2016)

What was the Green Revolution?

In short, the Green Revolution sought to apply the technologies and tools of US industrial agriculture in the Global South--an effort financed by large philanthropic foundations, namely the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations. It hinged on five main pillars: 1) high-yielding seed varieties, grown as monocultures, 2) chemical inputs, including synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, 3) mechanization, 4) irrigation, and 5) public science institutes that connected farmers with research through extension services.

The conditions that made the Green Revolution possible began in the early 20th century, with corporate consolidation and the establishment of huge tax-exempt philanthropies by industrial capitalists. Additionally, its emphasis on industrial agricultural methods hinged on the development of nitrogen fertilizers, produced from a fossil fuel-intensive method of artificial nitrogen fixation that was first used to produce ammonium nitrates used in explosives during World War I and was then converted toward agricultural applications after the war.

Print ad for Commercial Solvents Corp Hi-D Ammonium Farm Fertilizer, 1957

The Green Revolution officially began in the 1940s in Mexico, when the Rockefeller Foundation invested in the Mexican Agricultural Program. This occurred in the context of the election of the anti-Communist president Manuel Camacho, who forged strong ties with the US and with the Foundation. In 1944 the young biologist Norman Borlaug, later called the “Father of the Green Revolution,” was hired by the Mexican Agricultural Program, and in 1954 he developed dwarf “miracle” wheat stocks that permitted higher yields. The emphasis on wheat (rather than maize, which is more widely grown and consumed in Mexico) benefited commercial rather than small-scale farmers, as demonstrated by the fact that in 1960, wheat yields were 50 percent higher on private properties (larger than five hectares) than on ejidos (communal agricultural land) and small private properties. Thus, the Mexican Agricultural Program aligned with the needs of a very particular group of farmers, whose resources were greater and who tended to be located in Northern Mexico.

Norman Borlaug (standing in upper center-left) with students in Mexico, 1964 (source: Wessel’s Living History Farm)

From there, the Green Revolution was instituted in numerous Asian countries, including India and the Philippines, from the 1950s to the 1970s.

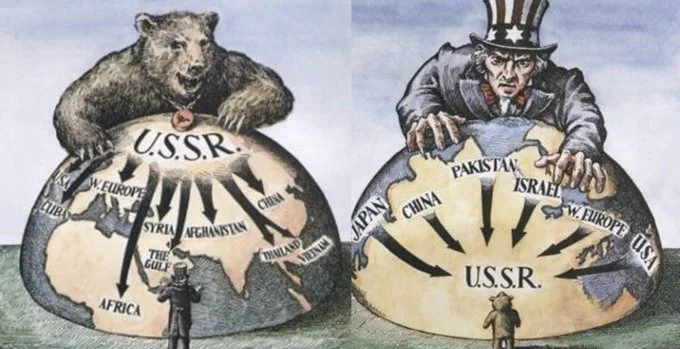

At its peak in the 1960s and 1970s, the Green Revolution was expressly aimed at curbing the spread of communism into poorer and rural areas in the Global South. The term itself was coined by William Gaud, of the US Agency for International Development (USAID), in 1968 at a meeting of the Society for International Development in Washington, D.C. Describing increases in global food production as a result of US and philanthropic funding for fertilizer, irrigation, and hybrid seeds, Gaud stated:

“These and other developments in the field of agriculture contain the makings of a new revolution. It is not a violent Red Revolution like that of the Soviets, nor is it a White Revolution like that of the Shah of Iran. I call it the Green Revolution.”

The Cold War imagined from a US perspective (left) and a Soviet perspective (right). Credit: Ingram Pinn, printed in Jon Connell, "Who can prevent a war of the worlds?" Sunday Times, 29 Nov. 1981, reprinted here

The fear of communism was also made explicit within the Rockefeller Foundation. The Board (including John D. Rockefeller III, during his tenure from 1946 to 1956) believed that agricultural development would reduce population growth in Asia — seen as a key factor in increasing impoverishment and hunger and making people more amenable to communism.

The impacts of the Green Revolution

With the application of industrial methods (especially fertilizer use) in much of the Global South, the food available per person in the world rose by 11 percent over the two decades of the Green Revolution, while the estimated number of hungry people fell from 942 million to 786 million – a 16 percent drop.

However, there are a number of critiques of these statistics and their attribution to the Green Revolution:

In India, yields increased in this period due to factors not directly linked to the Green Revolution, including increased precipitation and higher market prices that compelled farmers to plant more land in commodity crops.

Furthermore, the inputs used in Green Revolution agriculture were highly dependent on subsidies and price supports. Under a food self-sufficiency program in the Philippines that began in the mid-1960s, price supports for rice increased by 50 percent. In Mexico, the government purchased domestically grown wheat at 33 percent above world market prices, and India and Pakistan paid 100 percent more for their wheat. Because of the high cost of these subsidies and price support programs, the US government increasingly supplanted philanthropic foundations in assuming the Green Revolution’s fiscal commitments through the 1960s – amounting to USD 3 billion a year in the mid-1960s. With the end of the Cold War and the rise of neoliberalism and Structural Adjustment Programs, this level of governmental support dried up; this increased the costs to farmers of inputs and therefore led to increased indebtedness.

Although India is widely viewed as a Green Revolution “success” story, increased productivity also did not translate into dramatic reductions in hunger. As of 2006, 21.7 percent of the population was estimated to experience hunger. This marks only a very modest decrease from estimates of 25 percent in the 1970s, when the Green Revolution was still taking hold. Largely due to government-sponsored programs, the rate of hunger decreased to 14 percent in 2020 — yet this is still extremely high, comprising 189.2 million people, and means that India ranks 94th out of 107 countries on the Global Hunger Index (see Figure 1), despite the production of cereal grains continuing to increase.

The Green Revolution has also caused numerous environmental problems, further eroding farmers’ resilience. Desperate attempts to reap higher and higher yields led to a host of cyclical problems, such as the loss of biodiversity and the increased vulnerability of plants to disease. For example:

Increased pesticide use led to resistant strains of pests and as well as insect vectors of human and animal disease in the same environment. To combat the resistance in pests and achieve desired yields, farmers across the globe have been encouraged to use more virulent pesticides and/or to increase the dose of pesticides, resulting in higher amounts of toxic residues in soil and food consumed by humans and animals worldwide. Consequently, the overuse of toxic pesticides over the last four decades of the Green Revolution practice resulted in soil degradation, water pollution, and human health problems. However, studies show that these technological solutions, coupled with governments’ Green Revolution strategies, failed to benefit farmers.

High-yielding varieties are also extremely water-intensive. Historically, civilizations across the globe relied on rain-fed crops which secured food, nutrition, water and soil health for their communities. In places that experienced periodic droughts, more drought-tolerant crops were grown alongside other cereals to minimize the impacts and ensure food supply, even in bad years. Smallholder farmers developed ingenious ecological methods to manage and conserve natural resources, including water. However, the Green Revolution marked an end to such conservation practices by moving towards a culture of extraction. After 1970, India witnessed a shift from traditional rain-fed millets, oilseeds, and pulses suitable to local environments to remunerative and irrigation-intensive crops, such as sugar cane and rice. This led to:

1) increased run-off of soil nutrients

2) a rise in malnutrition, due to the decline in nutrition-rich indigenous crops, and

3) water stress and related conflicts between regions.

Finally, the increases in yields from the Green Revolution and industrial agriculture track with attendant increases in the use of fossil fuels —especially from nitrogen fertilizers (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Increases in cereals production have been made possible through increased application of nitrogenous fertilizers (source: United Nations Environment Program)

For most of human history, nitrogen was one of the main limiting factors of agricultural production. Nitrogen comprises 78 percent of the atmosphere, but in a form that is unusable to plants. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a rush for nitrogen-rich guano and sodium nitrates transformed Latin American economies and transnational labor relations. And then, during World War I, Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch developed a process for using hydrogen and atmospheric nitrogen, plus natural gas and water, to synthesize ammonia (NH3), which is more readily usable by plants. This is called industrial fixation, as opposed to biological fixation, which occurs in “closed systems” when legumes’ roots form symbiotic relationships with soil bacteria that can process nitrogen into ammonia. Industrial fixation now forms the vast majority of nitrogen fixation that happens on Earth (see Figure 3). From the perspective of climate change, the problem is that industrial fixation requires huge amounts of energy from fossil fuels. The Haber-Bosch process relies on high temperature, high pressure, and hydrogen atoms ripped from fossil fuels. It burns natural gas (3 to 5 percent of the world's total production) and accounts for approximately 1.2 percent of the world's carbon emissions. Additionally, nitrogen fertilizer application on farms has increased emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O), a greenhouse gas with a warming potential considerably higher than CO2.

Figure 3: The nitrogen cycle within the EU-27. Note the difference in line sizes between biological fixation (natural N2 fixation and crop N2 fixation) and industrial fixation via fertilizer production (large blue arrow). (source: Fowler and Coyle, 2013)

Overall, the Green Revolution increased farmers’ vulnerability to ecological problems (like years with low rainfall) and global prices of fossil fuels and chemical inputs. This has led to widespread unpredictability about the continued ability to keep up with and afford the demands of the industrial agricultural system.

While the Green Revolution transformed agriculture in much of Latin America and Asia, its proponents suggested that it bypassed Africa. Although this was not strictly true, Green Revolution-style methods did not take hold in most of the continent, due to various ecological, social, and political particularities, as well as changes in the global economy (including the impacts of structural adjustment on African states and agricultural systems). Thus, in 2004, Kofi Annan, then-Secretary General of the United Nations called for a “uniquely African Green Revolution.” Taking up this call, the Gates Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation founded the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) with an initial grant of $150 million in 2006, claiming that this “Green Revolution 2.0” would extend the yield gains of the first Green Revolution to Africa, while learning from its failures.

SOURCEs and additional reading:

Raj Patel (2013), The Long Green Revolution, in the Journal of Peasant Studies

William S. Gaud (8 Mar 1968), The Green Revolution: Accomplishments and Apprehensions

Nick Cullather (2011), The Hungry World: America’s Cold War Battle Against Poverty in Asia

Tarek Radwan (2020), The Impact and Influence of International Financial Institutions on the Economies of the Middle East and North Africa, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung

Colin Clark (1972), Extent of Hunger in India, in Economic and Political Weekly

India ranks 94th among 107 countries in Global Hunger Index; 14% population estimated to be undernourished (Oct 17, 2020), FirstPost

State of Hunger in India (nd), India Food Banking Network

FAO (2020), The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World

F. Thullner (1997), Impact of pesticide resistance and network for global pesticide resistance management based on a regional structure, in World Animal Review (FAO)

Ralf Schulz et al. (2021), Applied pesticide toxicity shifts toward plants and invertebrates, even in GM crops, in Science

Robert van den Bosch (1978), The Pesticide Conspiracy

The Pesticide Action Network North America, The Pesticide Treadmill

GRAIN (2008), Lessons from a Green Revolution in South Africa

Maha V. Singh (2008), Micronutrient Deficiencies in Crops and Soils in India, in Micronutrient Deficiencies in Global Crop Production

Charu Bahri (2018), How India Could Cut Irrigation Water By 33% – And Reduce Anaemia, Zinc Deficiency, Bloomberg

Ann Raeboline Lincy Eliazer Nelson, Kavitha Ravichandran, & Usha Antony (2019),The impact of the Green Revolution on indigenous crops of India, in the Journal of Ethnic Foods

Manu Moudgil (2016), Crop change for better yield? India Water Portal

OECD (2017), Water Risk Hotspots for Agriculture

GRAIN, Greenpeace International, and Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (1 Nov 2021), New research shows 50 year binge on chemical fertilisers must end to address climate change

United Nations Environment Programme (2012), The end to cheap oil: a threat to food security and an incentive to reduce fossil fuels in agriculture

Edward D. Melillo (2012), The First Green Revolution: Debt Peonage and the Making of the Nitrogen Fertilizer Trade, 1840–1930, in The American Historical Review

Vaclav Smil (2001), Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production

Jan Willem Erisman et al. (2008), How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world, in Nature Geoscience

Nicholas Gruber & James N. Galloway (2008), An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle, in Nature

Lu Wang et al. (2018), Greening Ammonia toward the Solar Ammonia Refinery, in Joule

Collin Smith, Alfred K. Hill, and Laura Torrente-Murciano (2020), Current and future role of Haber–Bosch ammonia in a carbon-free energy landscape, in Energy and Environmental Science

Leigh Krietsch Boerner (15 June 2019), Industrial ammonia production emits more CO2 than any other chemical-making reaction--chemists want to change that, Chemical and Engineering News

Thin Lei Win (7 Oct 2020), Nitrogen emissions from rising fertiliser use threaten climate goals, Reuters

Eric Holt-Giménez (2008), Out of AGRA: The Green Revolution returns to Africa, in Development; William G. Moseley, Judith Carney, and Laurence Becker (2010), Neoliberal policy, rural livelihoods, and urban food security in West Africa: A comparative study of The Gambia, Côte d'Ivoire, and Mali, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, William G. Moseley (2017), The New Green Revolution for Africa: A Political Ecology Critique, in the Brown Journal of World Affairs

United Nations (2004), Secretary-General calls for ‘uniquely African Green Revolution’ in 21st century [press release]

Anuradha Mittal with Melissa Moore (2009), Voices from Africa, Oakland Institute